Friday, December 14, 2012

Kinship Assignment - Anthropology

Let the sting of urea from the paint tingle your nostrils as you relax and watch the stranger tug at the bit of rope hanging by the right side of the wooden gate. The rope leads to the bell that clangs a good twelve feet high in the air of azure folded into cerulean. Relax. Relax and remember that you are bigger than all of this, stronger than any broken marriage, tougher than any of your mother’s romances. The gate that smells of urea and is tacky still to the touch, encloses the property and a house carved out of the stone of the side of the mountain and as you relax and let your eyes get heavy, she walks in with you and sees only a perfunctory living space carved out of the stone of the mountain, a family villa typifying the provincial architecture that is the skeleton of each and every one of these mountain top towns. Erase the windows of your mind and visualize a blue sky and let Zia tell you a story which I sincerely hope will help to ease your pain. Nonna Dina (your Nonna Lucia's mother) is re-latching the gate as she spits at the dirt and curses the misery of pigs, ushering in the stranger toward the darkness and the scant and ashen black and gray of the stone kitchen’s hearth. (This is the house where Nonno Primo, Nonna Lucia’s father was born. This is where he grew up and eventually where your Nonna Lucia spent the summers of her childhood. It is where your Nonna Lucia lies now, sickly in an upstairs bedroom. It is for her that the stranger comes. Ah, but her mother was nasty and foul tempered. It was the war. World War Two broke so many people and unfortunately our Nonna Dina was one of them.) So breathe in and picture Nonna Dina as she mutters a lamentation toward the unwelcome stranger, wiping the dried egg from her hands onto her apron briskly, turning the skin of her hands bright red. Execrating the day she ever thought it wise to marry into this God forsaken family and the nerve, the audacity this woman has of coming into her home. For what? Because she knew her mother-in-law? Because she know of our families’ lineage? Ma che disgrastiata. What a shame and disgrace. Because she knew her mother-in-law, that woman who was the cause of all her troubles. A dappled fawn appears in the doorway. A dappled white tailed fawn. Relax. Because she knew her mother-in-law as both a blessing and as a curse. The stranger steps around the plank-board table and draws closer to the eight stone steps that lead to the girl (your Nonna). Nonna Dina looks at the fawn. What is it doing here? What else aside from this strange woman and all her secret knowledge and bottles of scented oils could be responsible for all her troubles? What is she doing here? Hadn’t that wretched mother-in-law been of the same caste of people? Ma che shama! What a despicable shame! Questa magari, this magus, this sorcerer, what could she want with her and her child? Take your silly dappled fawn and go, and be off with you!

“Che cose vuole?” asks Nonna Dina. What do you want, in a tone of reproach.

“I’m here for the girl.” stated the stranger quite flatly. She makes no indication that gaining Nonna Dina’s approval is in any way important to her. “I knew your mother-in-law, Adele. I know what ails the child and how to heal her.” The stranger smiles at the fawn in the doorway. Breathe in and relax, dear.

Indignant as is her usual manner of deportment, Nonna Dina nods her head toward the eight stone steps carved into the stone outer wall. Ashen faced and stalwart, she leads the stranger up to the room where the child has lay stricken down for the past six months. People knew. People still knew. This magari lineage is inescapable. Such a shame, such an embarrassment! To be seen by her neighbors letting this Strega putana into her home! But what choice did she have the end? The child had not walked in six months, had not walked even as tremulously as the fawn. What choice did she have? She is tight lipped, her arms folded across her chest in resignation. With no attempt at even the lightest of pleasantries, she steps aside at the top of the stairs and indicates the well lit room at the top of the stairs to the right. The child lays in a wrought iron bed, limp and moribund. Her breathing is forced and a coarse rasp is heard as she grapples at the air for each breathe. Breathe in and breathe out, says the stranger to the girl. Breathe in sweet Lucia. There there now child, breathe in and breathe out. And the sky gleams clear and pristine blue and cerulean through the window as a breeze carries itself across the child’s bed. The stranger turns her back to the indignant non-believer in the hallway of stone. She has no interest in sharing what she is about to do. Carefully searching through the pockets of her skirt, she retrieves a small pair of finely etched sterling silver sewing scissors. She cuts a lock of hair from the nape of sweet Lucia’s sweat soaked neck and recites the following incantation: No light shall die that dwells within. Your spark internal sustains you. On upswept wings alight the wind. Send her west where the light shall reclaim her.

The girl reaches faintly for the stranger’s wrist. The heat emanating from the tender tips of her fingers rests against the cool soft flesh of the stranger’s wrist. “The fawn” breathes the little girl without opening her eyes. “The fawn belongs to her. Take it with you.”

The stranger nods and agrees. She turns, tucking the lock of hair in her skirt pocket and brushes past Nonna Dina flowing down the stone steps to the plank-board table and the cold and lifeless hearth. Nonna Dina is deeply offended. She follows the stranger, both curious and angry.

“That’s it? No liniment? No teas?” Nonna Dina is appalled that this strange woman whom she has let into her home has done nothing to aid her ailing daughter.

The stranger turns, imparting a thin lipped condescending smile upon this dolt of a simple woman. How often it happens that women of means have no meaningful thoughts in their heads beyond the quality of their curtains.

“The child shall walk by tomorrow morning. I can let myself out.” The stranger makes her way around the backside of the plank-board table and out to the dirt foyer before the game-pole. She looks back into the dank cold darkness.

“Your hearth is cold?” It was more a knowing statement than a question. “How can you make bread?”

“My bread is fine!” chortles Nonna Dina. In high animation she snatches the gold and purple matchbox from the table and takes out a pungent long slender match to strike.

“Relax” says the stranger as she glances over at the knots in the wooden beams of the game-pole. She smiles and looks down at the fawn. She sees the dark film of miasmic energy as it lays softly about the parameter of the house. She recalls the day it appeared. The day the bombs dropped from German bi-planes cutting the bloodline. The day the magari ceased to be in this house. The searing, eerie whistles and hissing and then silence … the looming silence before the boon of the bomb would sound and her lifeless body struck the ground in between the latticed grapevines of the garden’s rich black soil. She smiles at the fawn who shows no fear. It walks toward her, begging passage in exchange for unconditional love. The stranger waits as the fawn draws nearer, then makes her way down and around past the dahlias and delphiniums, and out the freshly painted gate, the fawn in tow.

The preceding is taken from my fictional account of my mother’s bought with La Mal’Occhio ( the evil eye) in 1949. In this one of my family’s many old stories lie the seeds of my socialization and enculturation as a first generation Italian-American, as a Catholic, and as a member of a secret Italian lineage tradition called Stregonerhea. The surnames that have sculpted the clay of my being are Ercolani, Barbarini, Dentici/e, Terwilliger, Higgins, Clark, Crabb, Merritt, Ronald, Brady and finally Irwin. While each of these surnames have left their mark, it is the stories passed down from my grandparents more than my technical genealogy that I have found myself in. Those stories offered me a slightly different perspective than the ones found in the kitchens and on the front stoops of Brighten Beach, Brooklyn or Latina, Italy. Much of my self-definition has over time leaned more on my Italian-ness than on my father’s Dutch and Irish heritage. This is not for a lack of old stories, but more due to the fact that I am the fourth generation of Irish descendants who seem perfectly happy to be gentrified Americans and have no problem with the fact that they have willingly lost touch with their native language and customs of their mother country. And my Dutch family is completely estranged and unknown to me due to the rampant mental illness therein. Having corrected my mother’s English since I could speak it myself, I am keenly aware of her continuous connection to Italy and thus her and by extension my “other-ness”.

I was born in Fitzsimmons Army Hospital on Lowry Air Force Base to an American Air Force private and his foreign bride at the height of the social revolution of the nineteen sixties. This is the thesis of who I am. It has been my privilege to watch both my family’s and the country’s definition of kinship change over the past forty-five years. The issue of divorce, once a deviant form of behavior, has been common place in my family since 1948. This is in part due to religious tension, but is also due to alcoholism and mental illness both here in America as well as in Italy. The first divorces in my family were handled with so much shame that each father was completely erased from the family's appearance so as to seem “normal” to the neighbors. Thus both my biological father and I have no knowledge of his father's family. Ironically, finding the Terwilliger line on Ancestry.com was the easiest to follow due to it being patrilineal and based here in the United States for generations. My aunt in Italy found herself divorced after her husband could no longer contend with her post traumatic stress due to having been raped by a German soldier during World War Two. Her husband went so far as to have my aunt declared unfit and have their children institutionalized in orphanages until they each came of age. Thankfully the cultural issue of divorce, through becoming more common place, has begun to be handled more effectively. In my own two divorces my pre-liminal phase was one of mental illness which facilitated an inability to form healthy attachments. It is the combination of religious tension and mental illness that has informed and re-socialized and re-enculturated me through the rites of passage leading to adulthood. As divorce and mental illness are my anti-thesis, proper mental health care and religion have brought me through these rites of passage and my post liminal phase is now one of being happily married and mentally healthy.

Stress has been the universal response of everyone who ever dared to step a toe outside the Catholic Church. As is evidenced in the above work of fiction, my great grand-mother’s reputation as a strega/magari was still well known even after she died amidst a German air raid during WWII. So the fact that some strange woman who had clearly been a friend of my great grand-mother’s showed up one day to save my mother from the brink of death was extremely disconcerting to my grand-mother. My grand-mother had not known that her husband’s mother was a Strega (witch) when they had married and so was understandably shocked and embarrassed once she found out. Her relationship with her mother-in-law had always been strained as a result. But my great-grandmother was a temperate woman and so knew how to walk the line as a “good Catholic”. Even as a child visiting the family home in Castelviscardo, we went to church every day and the altar in the house was set up in veneration to la Madonna Negra. It was not until I was older that I understood that a statue of a black Madonna as opposed to a white one carried a vastly different meaning.

In 1975, amid her fieldwork in pre-Christian Italian medical anthropology, my mother managed to trip over what had over time become our family’s forgotten heritage. In her interviews with the elders of Castelviscardo over that summer she discovered we were Strega descendants. A Strega is usually a spiritual healer who worships Etruscan or Sicilian Gods exclusively, but often times, as is the case in our family, these healers are followers of the cult of the black Madonna thereby infusing their worship of pagan gods with Catholicism. Animism is a part of all of this as well. Having been raised to be a good Catholic by my grand-mother, my mother, while tickled by this information, managed to keep it a secret from my father for the remainder of their marriage out of fear of reprisal. But I had been in tow that whole summer. I carried around that big clunky tape recorder and listened in on every interview and the thought of being a witch delighted my imagination to no end. I began referring to my mother as “the queen of ‘no’” in response to her constant attempts to suppress my detective work on the matter. But what I did not understand as a child was the culture bound idea of secrecy and suppression that had come to surround Stregonerhea in Italy out of necessity as a means of protection against the Catholic Church. This culture bound concept has been shed by the many Streghe here in America today thanks to a handy dandy little thing we have here called the first amendment. In fact this year marked the first time Rome has ever hosted a Pagan Pride Day. Similar events were held this year here in both Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Interestingly, the Wiccans who are the majority of the attendees to these events all claim as their primary research materials on modern day witchcraft works of research that all originated in Italy (Leland, Gardner, and Crowley).The last fifteen years has also seen a dramatic rise in the number of “out of the broom closet” Streghe, in large part because of the internet. It seems that walking between the worlds is now defined as cyber-reality.

Here, on the other side of the pond, a different kind of religious tension was finding its way to synthesis in Brooklyn when my paternal great grandmother and great grandfather met and fell in love in Brighton Beach around 1919. The story goes that after they were secretly wed, both my grandma Lillian and my grandpa Willie each remained in their respective parents’ homes because grandpa Willie was an Irish Protestant and grandma Lillian was a Catholic. Grandma Lillian’s parents found out she had married that Protestant boy two weeks later and she was turned out of her house with one suitcase and did not speak to her parents again for another two years when she gave birth to my great aunt Mildred. It seems that Grandpa Willie had converted in the years between their wedding and the birth of my great aunt and so the provisional synthesis in this instance came in the form of religious acceptance along with the softening of the veneer of pride via the arrival of a grandchild.

As the daughter of an anthropologist, I would listen to these old stories and beyond the stories themselves, I found myself wondering exactly what had loosed the bonds of Catholic sub-culture over the past century. Is it the growing agnostic nature of American life, is it the disappointments brought about by the church scandal, or is it just cultural diffusion? Perhaps it’s a little bit of all three factors. I remember my father telling me how Grandpa Willie spanked him once for leaving his bike out on the front stoop. My Dad had told Grandpa Willie, “It’s okay Grandpa. They’re all Catholics.” To which Grandpa Willie responded, “Son, those are the worst kind.”

The concept of identity is also one that has touched my family and my own enculturation. After World War Two, my grandmother convinced my maternal grandfather to change the spelling of our last name from Dentici, which was thought to be a low brow country name, to the more prestigious sounding Dentice. My grandmother’s reasoning once again had to do with getting away from the peasant reputation of my grandfathers birth. Interestingly, after my grandmother’s death in 1991, my uncle changed the spelling of his last name back to its original form. He had never felt ashamed of being Castellesi (from Castelviscardo, a town with a population of 1500). In the Strega tradition, one’s name is what informs the development of personality. Being from humble means was apparently too embarrassing for my maternal grandmother. But after her passing, the rest of our family in Italy seemed to embrace the original spelling as a means of embracing our collective humility as well as our authentic selves. It seems some of us are not so afraid of what we see in the looking glass.

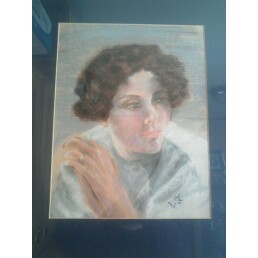

I too have felt the sting of ever changing identity via being adopted by my step-father and thus receiving his last name and then receiving the last names of all three of my husbands. This has meant that my last name has changed five times. I have looked into the looking glass and seen too many different people. In response to watching me struggle with my every changing identity, my sister from my mother’s second marriage has held firm to her maiden name and has refused to take her husband’s last name. While our grand-mother looked for prestige in the name that labeled her, my sister and I, like my Uncle in Italy are simply looking for our authentic selves. I tried to keep my maiden name when my third husband and I got married, but he is a very traditional man and would not hear of it. I believe my sister won her battle with her husband due to having been born after the feminist revolution in the seventies and thus in many ways she was born to a different version of our mother. I am far more like the Italian lady on the cover of this paper. I acquiesce. In my search for my more authentic self, I chose to take my husband’s name and be “Mrs. Michael Irwin”. However in my writing I will not give credit to any man whose label I have ever been identified with. My pen name is Ercolani: the maiden name of the last Strega in our family.

The dizzying phases of identity would not have been such an important issue to me had it not been for the restless and volatile childhood I shared with young and unhealthy parents. In 1981, our family pediatrician diagnosed me as manic-depressive. I was fourteen and had just survived my parents' divorce. I felt strongly that my volatile emotions were completely valid given my life circumstances at the time. It would take two more doctors and another twenty-five years before I would succumb to the diagnoses, now renamed bi-polar disorder. As I look back on those twenty-five years of symptomatic behavior, I see why every annihilated family relationship occurred. I also see in retrospect who else suffered from this genetic disorder and thus who passed it down to whom. Each divorce, including the one between my paternal grandfather and grandmother in 1948 was the result of an untreated mentally ill spouse who drank to excess and was abusive. Thus Grandpa Bob, my biological paternal grandfather most definitely had it because my biological father was diagnosed with it a few years after I was. The three of us have been the ostracized and the notorious and violent black sheep of the family all our lives. I have my suspicions that my paternal great grandfather also suffered from it because he died of delirium tremors and bi-polar disorder has affected other cousins on the Irish side of my family as well. Bi-polar people suffer from racing thoughts, insomnia, visual and auditory hallucinations, and magnified emotions that can lead to abusive outbursts. Many people self medicate with drugs and alcohol because they know something is wrong but fear the stigma of a psychological diagnoses. Most of the afflicted in my family have coped by becoming closet addicts who turn to the church for help. My father and one second cousin coped for years by drinking their marriages to death and faithfully attending eight thirty mass every morning. The only person who was willing to talk about the elephant in the room was the family heathen. (That would be me.)

When I think of how I coped with my illness for so many years I think of my childhood as that pre-liminal phase, in which I had no idea that I had a bi-polar father and a mom who had PTSD. Now I look back on how each unhealthy family member all relied on their respective tenets of faith and I can't help but think of the epiphanies of William Blake or the visions had by Allen Ginsberg. We are all self seeking wounded healers to a fault. This phase of visions, of hearing voices and of alcoholic black outs that leave destroyed relationships in their wake was unquestionably the liminal phase for each of us. Each of us who suffered were creative, sensitive and artistic. Each of us was ill equipped to over-come the ravine our self esteem had fallen into. I remember begging my paternal grandmother to let me go to therapy only to be told, “You don't need any of the psychological crap. You just need to be around your family.” But as I grew up and looked more closely at my grandmother, I saw the daughter of the man who died of delirium tremors. I saw the girl who was valedictorian of her high school class in Brooklyn, a high school of seven thousand students, who was told she could not attend college because “nice girls don't go to college”. I saw in her someone who had been told no all of her life and who at the end of her life suffered from deep chronic depression, sleeping much of every day away. She never got to reach her post liminal phase.

And so it it the woman on the cover of this paper once again who I have modeled myself after that ultimately empowered me with the tools of my own recovery. I am the daughter of a woman who had the wherewithal to get the hell away from an Italian family drowning in PTSD in 1966. I am the daughter of a woman who is the only member of her family to come and make a life for herself in a completely foreign environment. I am the daughter of a woman who made a life threatening mistake by marrying an abusive mentally ill alcoholic in a foreign country and who as a result lived and anomic life for many years until she finally became re-socialized and re-enculturated as an American with friends and peers of her own.. I am the daughter of an art major turned anthropologist, who took the creative skills of observe and report and turned them into learning experiences that helped her to understand her new life here in America.

Two days after my diagnoses and the afternoon after my mother managed to get me out of psychiatric lock-up, she and I sat on the couch in my apartment in Harlem and discussed what my illness actually meant. She told me of how in many cultures, it is the mentally ill who are chosen to be the shamans of the tribe. I thought of how my cousins and my dad and I all dove feet first into our spiritual lives in an attempt to heal ourselves. Then I thought of the Italian great grandmother who I had eventually learned how to channel and I asked her what her thoughts on the matter might be. This is what she said:

There had been a curse put on the family. By whom and what for I have never been able to tell. The towns people had always been jealous of my ability to earn an income for myself in spite of the fact that my husband left me so some jealous woman may have been the cause of it. But it began the day your Nonno married that Dina. They say the fires of a family's hearth refuse to light when there is no more love in the house and your grand mother was a love-less woman. Three deaths would be the cost of this curse before it could be lifted. I was the first. Then your Zia Gabriella, your namesake, and then finally your cousin Paula. Ah but you Gabriellina, cara mia have figured it out. And now the hearths all burn bright, and the bread starter lives once again.

It is interesting to me that my path to recovery began upon the advice of a Pagan Shaman named Andras Corben Arthen in Cambridge, Massachusetts back in 1990. He told me that the best form of therapy for “people like us” was Jungian dream analysis. And so it was for seven years that I exorcised daemons in the form of dreams and visions. The Jungians however do not believe in medication and so the ripple effects of my emotional flailing took a tremendous toll on my family. This is a large part of why I no longer have a relationship with my father's side of the family. Being devout Catholics, they had little patience for my pagan antics. But my mother understood that this was all part of my vision quest pathway out of darkness. When I came to Ohio, the life lessons that would lead me to stop scapegoating my problems came to pass: yet more face down in the mud rites of passage.

Is my fascination with my great grandmother and her Strega faith what C. Wright Mills called the sociological imagination? Did I used those old stories as escape fantasies? Maybe. But I don't think so. I think we hold onto the legends that are told to us by the fireplace after mom has had too much sangria and we macrame those stories into the fiber of our being. The fawn in my mother's vision has manifest in my marrying a deer hunter. Our animism states that a stag or a doe is a symbol of unconditional love. The hearth in her vision is equally important. A hearth that cannot hold a fire is said to be one that is cursed and is only found in families that have forgotten how to love one another. Now both my mother and I have fireplaces: hearths upon which we may bake bread. These fireplaces are warm. They burn bright now that the issues of mental illness have all been healed and the greatest magic of all has been restored: love. You had mentioned at the beginning of this semester that often amid these assignments, students manage to rekindle splintered family relationships. You were right. My Dad has been diagnosed and is on meds now. He wants to apologize. This is my story. Nobody came over on the Mayflower and nobody in either Ireland, Holland, or Italy had birth certificates prior to 1900. But I don't care about that. All I care about is retrieving from my past that which will grant me a brighter future.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment